In October 2020, before the land fell into autumn and another state of lockdown, I happened to be on Devon’s south-east coast. Where I remembered nearby Exeter and that phonetic connection with its predecessor, Roman Isca. Or ‘Isca Dumnoniorum’to be precise – Rome’s citadel for the soldiers and tax-gatherers they imposed on local tribes. So we jumped into the car and drove a short way west to find what remains of Rome, to see how much of Isca is extant at Exeter – which is more than you’d think.

In AD 43, when the Roman army arrived on the Kent coast – but unlike Julius Caesar, one hundred years before – they planned no passing visit. By AD 55, and despite twelve years of dogged British resistance, five-thousand ’ironsides’from Vespasian’s Second Legion (led by an emperor-to-be) had rampaged across Dorset, capturing hillfort after hillfort. By AD 55 they’ve also taken Devon, arriving finally here at Isca to establish their first fortress on its hill to see out the winter. The topography around so many of these old, legionary fortresses still speaks of Roman arrogance or confidence, and the same is true at Isca, its setting instantly reminiscent of Chester or Lincoln when viewed from their walls. Standing up here and raising your eye above modern rooftops, it’s easy to envisage that insecurity typical of an invading army – bivouacked in the field and surrounded on all sides by hostiles in the trees. As the blue, forested hills of Wales encircle Chester to this day, so would the Dumnoni around Isca. Tribesmen hiding-up unseen among their Devon greenwoods – hating and hiding, while legionaries in camp imagine an implacable, invisible enemy, camouflaged with woad.

Just when it seems like Rome has won and barely six years later, Isca’s resident Second Augusta spoils its hard-won reputation during Boudicca’s bloody rebellion of AD 61 – when its acting commander, Poenius Posthumus, prefect of the camp, disobeys a direct order from Suetonius Paulinus, Rome’s provincial governor in the field. Despite Paulinus’s urgent order to march east from Isca and help save the province, Posthumus declines his request. Leaving Londinium to burn, and Paulinus to try and recover Britannia alone with whatever troops were left. Outnumbered three to one, Paulinus somehow still manages it – stopping Boudicca dead in her tracks, somewhere in the Midlands. High on Isca’s central hill, Posthumus commits suicide as soon as he hears. With Boudicca dead, further resistance to Rome in the South West is futile and soon ebbs away, the need for a legion with it. By AD 75, the Second Augusta has marched out of Isca towards Caerleon in South Wales, which would remain the legion’s permanent depot for another two centuries at least.

In the social vacuum created by their departure, what began as an armed camp to the legion is soon transformed into a regular town – civic capital to a Romanised tribe. ‘Isca Dumnoniorum’develops fast – within twenty five years, there are public baths and a forum here; high on a hill whose elevated promontory projects towards the marshes of the River Exe, standing protected to the north and west by deep ravines and high cliffs. Somewhere safe for civilians to live and work, where suddenly there are prospects and life’s looking good. As the legion was once supplied in bulk by the ships and barges which navigate the River Exe and its estuary, so the sea trade now beckons and it seems merchants are everywhere. A busy hundred years go by without anyone noticing, and the world’s changed again – in the reign of the philosopher-emperor, Marcus Aurelius, construction work begins on an impressive new perimeter. Defensive stone walls and towers rise to protect a much larger town but hint at new threats, some of them Irish. What was fortified boundary to a forty-odd acre rectangle inherited from the legion expands to encompass more than twice that land. Walls crafted from a hard rock they quarry from an extinct volcano up at what the Normans would later call ‘Rougemont’, the old red hill in the north-east quadrant of this city. Running for approximately one-and-a-half miles and up to ten feet thick, twenty five feet high, these defences may have been raised first against the Celt but are undoubtedly intended for a wider audience – asserting Roman power.

The new enclosure to urbanism whose maximum extent now exceeds ninety acres in total only confirms how important this centre has become. Let another two centuries go by from its early expansion, and whilst Isca might still believe itself Roman, Dumnonian farmers still bringing their produce into market like their forefathers did; the latest word down in the forum is of how a great emperor far away in the east has been baptised on his death-bed into the new Church of Christ.

While his bereaved empire’s Rhine and Danube frontiers buckle under increasing attacks from Germanic barbarians, Constantine the Great’s successors as emperor fight off usurper after usurper in an endless cycle of internal struggles for power – yet more civil wars. No wonder then, that by AD 367 – the year of the ‘Great Barbarian Conspiracy’ when both Saxons, Picts, and the Attacotti of Ireland plot to attack a tottering province together – even modern archaeologists can detect how much Isca Dumnoniorum seems to have shrunk, as disease, dereliction, and decline creep inexorably in.

By AD 410, their chicken-coping emperor Honorius issues that final, hand-washing rescript advising his embattled province of Britain to look to its own defences; and whatever’s left of the mighty Roman legions are finally gone from this island. Gone to defend the indefensible against overwhelming odds. Though if their empire was lost – Britannia and Isca Dumnoniorum finally abandoned, perhaps a hundred years later – maybe there’s still flowering some successful defender of Roman tradition here in the South West. Perhaps a war-leader like ‘Artorius’ – what legend calls ‘Arthur’. Although if Isca’s involved, there’s little left from that era to survive as archaeology, even less to say whether its circuit of walls were by now even occupied. But the Anglo Saxon Chronicle will boast how successive invasion by Saxons become ever-more relentless – climaxing in AD 928, when their greatest king ever, peerless Athelstan, finally repairs an ancient circuit of walls first commissioned by some lost Roman garrison – Exeter being one of only four Saxon royal burghs in Devon.

Beyond whatever those outer walls might – or might not – tell us about the original fortress, little more Roman masonry from Exeter would be exposed until 1971 – ‘AD’ I should say – when a substantial military bathhouse dating from about 60-65 was discovered bang in front of a Cathedral founded in 1050; there on the lawn between its west front and the War Memorial.

Today, the Second’s bathhouse slumbers quietly under clipped grass and, when I entered the cathedral in October 2020, the person on duty at the till had no knowledge – although I hear from elsewhere there’s talk of disinterring its ruins for lottery-funded display. Which is not to say that Isca’s been forgotten in the meantime, because it was in 1954 that Rosemary Sutcliffe first published her seminal novel, ‘The Eagle of the Ninth’. The one where Marcus Flavius Aquila, orphaned son of a senior centurion in the ‘lost’(sic) Ninth Legion, is sent off to the ends of the earth. Sent out here to command a garrison of auxiliaries based at Isca Dumnoni,the frontier fort in the far west of Britannia whose outgoing commander is keen to warn him against will-o’-the-wisp Druids – peripatetic priests to the native Briton, who stir-up rebellion amongst any tribesmen willing to hear.Almost everything that Exeter represents today and which defines its long history occurred within this same walled enclosure. It was here where Romans lived and Poenius Posthumus committed suicide; where Saxons settled and the Danes laid waste. Liberated from Viking tyranny by Alfred the Great, then besieged by William the Conqueror.

A location for three great institutions of medieval life: the Norman castle, their cathedral, and the guildhall – together the beating economic, social, and political heart of this city for a thousand years. Later attacked by yet another usurper or pretender to power, by Perkin Warbeck in the sixteenth century, the city walls of Exeter would become surrounded and besieged twice more during the English Civil War; then bombed from the air by Luftwaffe aircraft during World War Two, who destroyed nearly as much of its half-timbered, mediaeval centre as they did Coventry’s.

Although still imposing, it’s sad to see how little is made of these walls – in October 2020, the reception desk inside Exeter Cathedral was at a loss to suggest anything of their Roman city which might survive above ground, and I was left to find it for myself.

Nor can you walk along the walls in Exeter as you might do in other walled cities of England, like York or Chester. That day I was there, increased infection amongst the student community had made Exeter into something of a ghost town but – unlike Chester or York – any suggestion these upstanding remnants might hark back to Rome seems almost downplayed. As if the city’s turned its back on them. Yet, properly managed and presented, they might provide a major feature for Exeter’s tourist industry; with guided tours for anyone interested in its history rather than its shops; whilst walking around below its ancient walls does at least offer you access on foot to some of the city’s few remaining attractive, historic areas. (Don’t even think of bringing a car here).

Yet, on leaving the Cathedral, my wanderings would reveal how large stretches of second-century Roman masonry can still be seen today, including sections of wall lucky to have escaped the modern bypass. Because it’s generally accepted that the purple-grey volcanic ‘trap’ seen in its upper two-thirds is original Roman stonework dating from the civitas of Isca Dumnoniorum. Characteristically square. However, changes in colour and style along the lower third are usually interpreted as where original ground levels have later eroded and earlier walling needed to be underpinned during the Middle Ages; using different types of stone, whatever was to hand.

By the time of the English Civil War the old city wall was tired and needed further repair; while new-style gun-batteries were being added along its southern and eastern sections, some of which remain. During not one but two sieges of Exeter – firstly in 1643, and then again in 1646 – the city wall was just component-part in a sophisticated system which included not only the new gun-batteries but a complex array of deep ditches and earthen ramparts. Although badly damaged by artillery in places, any gaps were at least repaired, but the Civil War represents the very last time these ancient walls would be relied upon in the active defence of Exeter.

Thereafter, the walls simply slide into obscurity. Houses were built right against them and the creeping Georgian or Victorian suburbs finally eliminated their tactical importance as city wall, as an important boundary or defence – although happily no-one (apart from the Luftwaffe and town-planners) would attempt to destroy it further. Because the greatest damage of all would occur during peacetime and our modern, post-war era. During the later Twentieth Century, when a particularly-long section near the old South Gate was completely demolished as part of major re-planning and rebuilding works happening right across the city.

Belated civic responses to the catastrophic Exeter ‘Blitz’ of May 1942 as, from the 1960s onwards – and outdoing both Cromwell and Hitler – local government uproots far more ancient walling to create a broad inner-bypass for the motor vehicle. (See photo). A tragedy for Exeter’s citizens and a triumph for Philistinism that’s doubtless comparable with whatever’s going on at the time in many other British cities. Places like Carlisle, for instance, where a similar dual-carriageway was driven directly between the city and its castle, severing pedestrian access. (Or maybe Newcastle-upon-Tyne). Taken from a built canyon seriously disfiguring Exeter to this day, my own photo’ illustrates how a shabby footbridge shunned by pedestrians spans this huge breach, carved into a circuit of walls which had otherwise survived pretty much complete until 1961. (Yet more significant Roman masonry was apparently buried behind Broadwalk House, across in Southernhay).

Fortunately, at least what’s left for us today survives intact, and is generally maintained. Although in 2020, were a disinterested observer to consider any part or portion neglected, maybe weed-grown, then such a situation could be longstanding? Because – back in February 2019 and despite Historic England having assessed their condition as “high risk” and “slowly deteriorating“(sic) only the year before (i.e. 2018) – it’s reported that a large section from these ancient Roman city walls suddenly fell into a public beer garden below. Happily, no-one was hurt, but it’s alarming to read that – despite surviving two thousand years and multiple sieges and bombings – this ancient wall’s huge stone blocks could so suddenly crumble into pieces, then allegedly fall onto a pub’s pergola, pieces of massy debris piled across the way. (A very similar episode reportedly occurring on Chester’s Roman city walls during 2020).

Because – if you can believe these stories in the press – modern Exeter has never been too good at this: at keeping safe, whatever’s left of Isca.

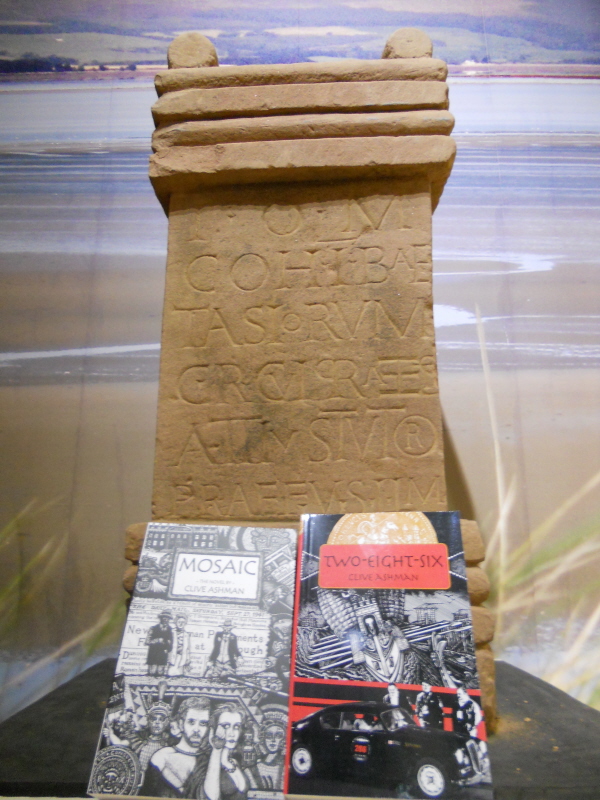

For another claimed example of that, let’s take an intriguing announcement made on 12th February 2018, where (under the banner headline: “MYSTERY OF EXETER’S MISSING ROMAN MOSAIC ART TREASURE”) the news website ‘Devon Live’ reported how a retired local art-dealer was trying to solve the mystery of Exeter’s missing Roman mosaic floor. With my first novel ‘MOSAIC’ being set around another missing Roman floor, this one stolen from a villa outside Hull in 1948, you can see why such a news item might catch my gimlet eye. In 2018 ‘Devon Live’ was reporting on how older residents of Exeter – with one good reason or another to visit their former police station and magistrates court in Waterbeer Street (demolished to build a new Guildhall Centre during the destructive 1960s) – could remember its entrance hall as decorated by a genuine Roman floor. First discovered when the police station was being built in 1887, the Victorian builders relaid it in situ. But if the missing mosaic had not been salvaged on demolition, for Exeter’s Royal Albert Museum (current custodians insist that, no, it never was….) then one alternative suggestion was that it might still survive, under a flowerbed in the Exeter Guildhall shopping centre……

Unfortunately, that idea’s apparently a definite ‘no-no’ too, because local historians and archivists were unanimous in confirming that – by 1972 at the very latest – this rare Roman floor had indeed been destroyed. (A familiar outcome for Hullensians – see the fate of the Brantingham mosaic, in my first book).

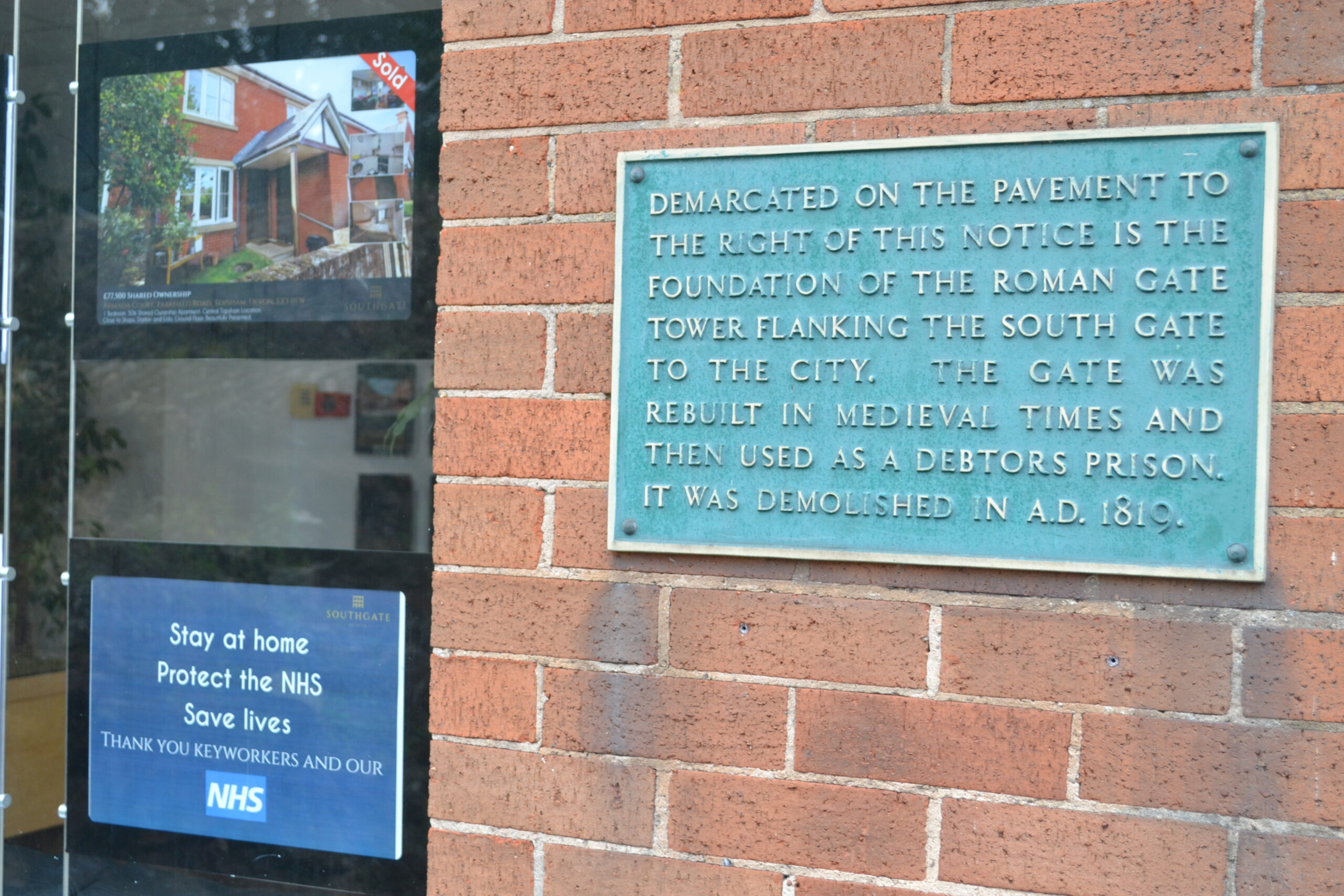

As an urban foundation from Britain’s early-Roman era, the city of Exeter and its strategic importance are vividly reflected in how strongly it has been fortified and fought-over during the long centuries following. Exeter’s Roman, Anglo-Saxon and medieval city walls define its soul and extent. They remain our most dramatic physical reminder today of its ancient significance; surviving as a roughly-rectangular enclosure of about 2.5 km in length, from which about 72% (1705m) is reportedly still visible as upstanding fabric, often up to 2.5m high. Of its four gateways, also of Roman origin (confirmed by excavations at the South Gate) most were taken down during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Repaired and rebuilt throughout succeeding Anglo Saxon, medieval and Civil War periods, it stands embellished by additional wall-turrets and bastions which – as at York – may equally be dateable to Roman, Anglo Saxon, or medieval periods; or maybe a mixture of each. As a majority of its residents undoubtedly do – all Exeter should be proud and celebrate the powerful evocations of its history contained in silent, venerable stones. Why I for one would hope that – once the current crisis is over – fresh effort and resources are applied to making rather more of them. Just as Isca deserves.

Clive Ashman – 29thNovember 2020

COMMENTS:

I very much enjoyed Clive’s round-up of Roman Exeter. At the rear of Marks and Spencers there is a protected section of Roman road. Customers just walk straight past it, but occasionally I have acted as a guide and drawn passers’-by attention to it, and there is genuine interest.

(Elaine Evans – 1st December 2020)

Thanks for mentioning this, Elaine – I definitely missed your Roman roadway, but it goes-to-prove-to-show. That the closer you look, the more there is to find …. archaeology by walking about!