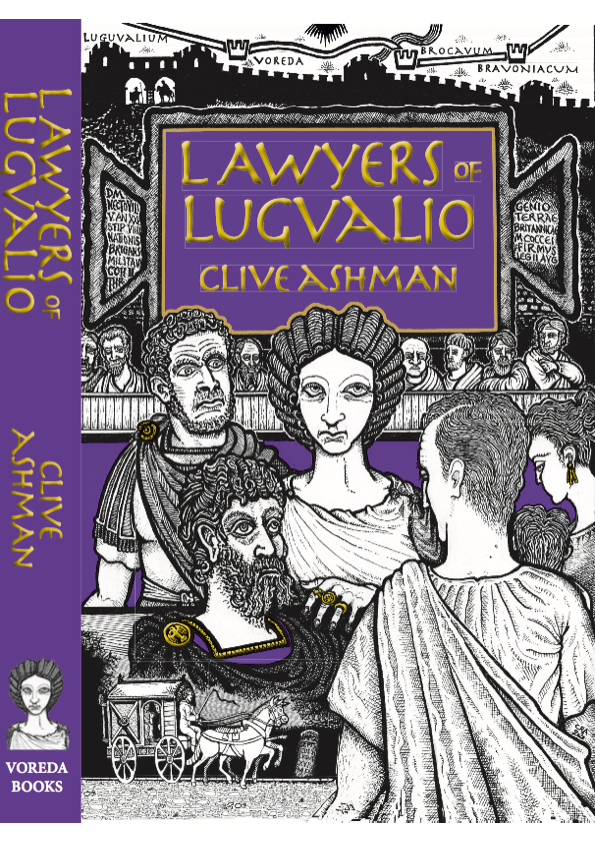

PROVINCE OF BRITANNIA – AD 208

“Wanting the quiet life in a wicked world, the advocate Justinus practices the law of Wills & Estates from the walled safety of Eboracum, his clients mostly dead.

But once work and funds run-out, bad debts and beneficiaries start chasing him, then it’s his senior clerk Tiro who finds a solution. In the shape of his wealthy new client – the lady Lydia Firma – who seems like the answer to his problems, when she’s only the start of his next. And an even better reason for them getting out of town…

Nine arduous days on the road with Lydia and her entourage that bring them – not without cost – before the Walls of Lugh.

To the frontier city of Lugvalio and Britannia’s wild west, where Justinus must confront Lydia’s notorious father, Marcus C. Firmus, in a court case more testing and terrifying than any known before.

For Justinus or Lydia, Firmus or Tiro – this bitter courtroom battle will prove the trial of their lives.“

‘WE ARE SLAVES TO THE LAW, THAT WE MIGHT BE FREE’

Officially launched in July 2021 at the ‘Petuaria Revisited‘ open day in Brough-on-Humber, East Yorkshire – site of the lost Roman theatre described in Clive’s MOSAIC. Later reviewed by David Pickup for The Law Society Gazette’s “BEST LAW BOOKS OF THE YEAR” 2021. Or Grasmere bookseller, Will Smith of ‘SAM READ’s, in his Christmas selection for CUMBRIA LIFE magazine. See:

https://www.lawgazette.co.uk/reviews/best-law-books-of-the-year-2021/5110557.article

"John Grisham meets Rosemary Sutcliff - meets Rumpole of the Bailey...?"

‘ LAWYERS of LUGVALIO ‘

AVAILABLE online HERE:

A brand new, author-signed 1st edition – direct from the official publisher.

Price to UK customers: £8.99 for (1 x) signed copy, plus £3.99 for UK (Royal Mail) post & packing.

(International buyers – please contact us for price & payment details first).

SPECIFICATION: ISBN: 978-0-9556398-4-5

Format: paperback bound, size 216 x 138mm – 320 pp. Including (2 x) Maps; an Author’s Note; Dramatis Personae; Glossary of place names & Latin terms; Bibliography & a Timeline of Roman BRITANNIA in the north.

With their book cover-designs & also maps as his own work, Clive Ashman’s original CV said “artist, writer, motor mechanic & qualified lawyer.“

But it’s time he spent with a trowel or giving guided tours – volunteering with professional archaeologists to help unearth the large Roman bathhouse first discovered at Carlisle Cricket Club (2017-18) which inspires this, his third novel set in Roman Britain. Its sequel, his fourth, following MOSAIC and then TWO-EIGHT-SIX – is now in preparation.

Begun during lockdown & completed on the eighteen-hundred-and-tenth anniversary of one of its protagonists actually dying at York – the Emperor Septimius Severus – LAWYERS of LUGVALIO starts in Scotland at a military outpost on their Antonine Wall.

Before moving south again, back to Roman York – Eboracum as was. Where the lawyer Justinus – out of work & out of funds – must begin his long trek north by road to Carlisle. Up to Lugvalio to fight his latest client’s cause – taking on far more along the way than anyone bargained for. Not just a trial…

Prefer to pay by BACS instead? See'CONTACT US'page to ask

You'd like a preview? Here's the prologue:

The Ochre Fort, Limes of Antoninus Pius, edge of Caledonia: AD 161-2

The centurion Marcus Firmus stood alone on the slumping turf rampart of his Ochre Fort and looked out onto endless sheets of rain. The best defence they had these days would seem to be the weather. If ever the clouds parted and the sun came out for longer than a week, then he feared for their safety, knew the tribes would come down. Marooned by an emperor’s order on this fortified border to malign wilderness, he and his men were sworn to defend a civilisation too many days’ march away to rescue them, for all its promising that one day they’ll withdraw.

Till then they must hold the line, await their fate with patience. Imagining that when his own nemesis appeared – as for anyone it must – then it would be swift and soon, arriving from the north.

When in reality she came later – from the south and slowly.

Burdened with unspoken tensions like these, while still looking outwards and north, he unconsciously grabbed a merlon off their timber battlement. A large piece of it came away in his hands – wet wood crumbling between his fingers like rotting flesh to snag on Apollo, engraved in his signet ring.

Firmus turned away in disgust. He nodded to a nearby sentry, shrouded in his soaking cloak, exchanged passwords, and then half-walked, half-slid down some slimy steps in the rampart-backing to rejoin the inner road. His dedicated suite of rooms were no less damp and disintegrating than any other barrack block where auxiliaries keep warm beside horses, but the difference here was privacy. He could get away from the men.

Soon he was comfortably settled beside a warming charcoal brazier, with an oil lamp for light, but his interlude of peace didn’t last for very long:

“What are you doing?” she said in a vexed voice, walking through the door.

“I’m reading.”

“Reading…?”

“Yes. A book.”

“It looks more like a rolled-up tent, to me.”

“It’s a scroll.”

“Oh, a ‘scroll’. What’s that?”

“It’s writing – marks, words made on vellum. A calfskin – you unroll it.”

“What’s it about – what do they say?”

“It’s Tacitus.”

“A Roman?”

“Of course. He’s writing about his father-in-law. A famous general called Agricola, who conquered these lands, long ago.”

“Well, he didn’t do a very good job of that, did he? Just look around you now.”

“It’s history, written about his father-in-law. With us, that means his wife’s father.”

“Is family important to you Romans?”

“Only when we’re dead. While you’re alive, they always let you down. But Tacitus was very proud of his relative. He was a great man, a great soldier. The tribes up here would tremble at his name.”

“Was?”

“Oh, yes. Agricola’s been dead a long time.”

“How long?”

“Must be sixty-five years at least, maybe more. Peacefully at home, in the reign of Domitian. But he campaigned all over Britannia once – and conquered Caledonia.”

“You said. And much good it’s done the lot of you.”

He’d never seen a tattooed woman before. It was something barbarians did. But here he was, entertaining one in his room: there’d be a scandal at home, if they knew. It was Epiclitus, the slaver, who’d brought her. The men had clubbed together with what pay they’d otherwise waste on gambling and bling to get themselves a whore for the fort. While away the winter nights. Epiclitus duly brought her up from the coast on a mule in fulfilment of their order, but from the very moment Firmus saw her, he couldn’t let it happen.

The men weren’t happy about it and there might have been a mutiny, except they had more sense, fearing the penalties. Humiliation, flogging, and death. So their centurion, Firmus, bought her for himself by paying a little more to the men, who despite making a tidy profit on the deal as a result still went away muttering, while Epiclitus didn’t mind one bit because he knew he’d got his price.

She remained his slave but, in the privacy of his room, that didn’t seem to matter, didn’t seem to count. As far as Firmus was concerned, and whatever others might think about slaves, she was a human being to him. And – by the light of his oil lamp – a very beautiful one, if difficult to grasp.

They had sex on a sheepskin in front of the brazier. He couldn’t call it ‘making love’ because her outlook on the matter was unknown, but it meant a lot to him and he needed the intimacy anyway, whatever she thought about that.

“Legum servi sumus ut liberi esse possimus” he’d whispered gently to her afterwards, breathing in her ear.

“So what does that pretty piece of Roman rubbish mean?” she said, stretching-out on her forearms like a puma he once saw in the Colosseum. It had just killed a convict, condemned to be tied to the stake. A man tethered like he is – unable to leave his post.

He smiled back: “We are slaves to the law, that we may be free…”